The long and the short of music notes: an introduction

Why the duration of notes depends on the context in which you’re playing or singing them

Apparently, I’m on my way to becoming a ‘podfaster’. A podfaster, in case you are just as much in the dark as I was, is someone who listens to a podcast at a faster speed than the original.

There are two camps; the fasters, who swear they’ll never go back to the ‘normal’ speed, and those who stand by their decision to stick with the original (remainers? No, that’s already taken. Sticklers?).

I am now firmly in the first camp, because it’s true that there is no going back, mostly because once you’re used to listening to conversations at a faster speed, the original can sound as if people are talking in slow motion.

But while the pace of a conversation might change, what doesn’t is the relative length of the words and the distance between them. If there’s a pause between the last two words at the slower speed it’s still going to be there when the whole thing speeds up. If the word on one side of the pause is only one syllable, it will obviously stay that way, and if the word on the other side is three syllables it won’t change, either. The only difference is that everything will last a little longer if the pace is slower, and not so long if the pace is quicker. Makes sense, right?

How music works: note lengths and the long and short of it

The same goes for music notes. You don’t need to be able to read music notation or understand music theory to get that there’s a variety of note lengths in music. Some are long, some are short, and some are in-between.

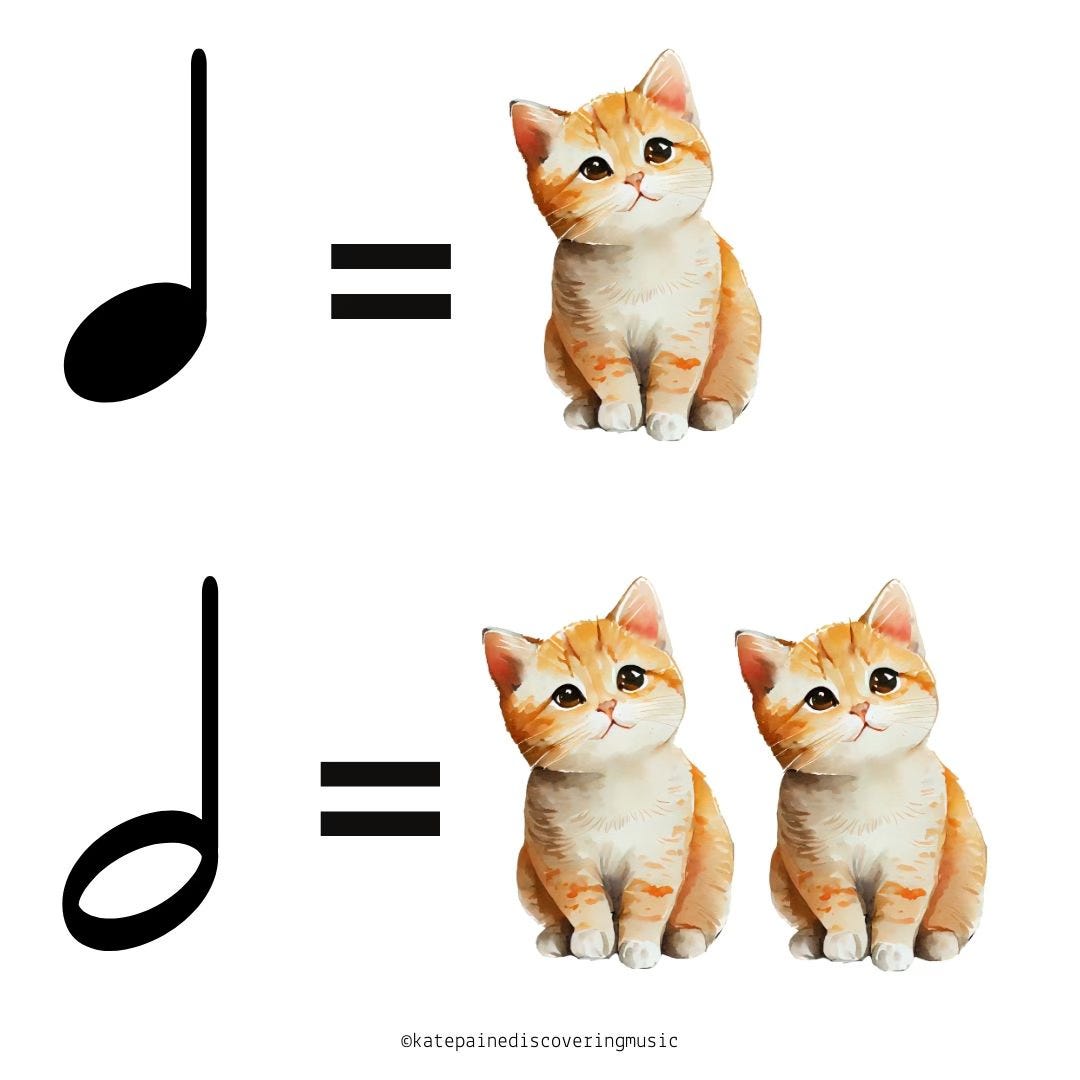

The notes have their own names, for example quarter note and half note (or crotchet and minim, depending on the country you’re in), and you can differentiate them by the way they look, too. Some are filled in and some aren’t, most have stems (like a flower) but some don’t, and some have dots to one side and others don’t. We also attribute a value to the notes. For example, a quarter note is one count and a half note is two, which means it lasts twice as long as the quarter note.

But what isn’t fixed is their duration. A quarter note might last much longer in one song than in another, and that half note might be much shorter in this song than it is in that one.

This seems crazy, at first. How can the duration of a note not be fixed when everything else about it is? What’s missing from this equation is the context in which the note is being played, and by that I mean the song or piece of music that the note is in.

It’s the speed of the piece—dependent, of course, on the person playing or singing it—that determines how long a note will last. If the song is fast, then the notes won’t last as long. If the same song is slow, then the those notes will last longer. But relative to each other, and within the song, a half note will last twice as long as a quarter note.

Remember, it’s just the same for the podcasts I like to listen to. If I speed them up, the words go by much more quickly than if I don’t. But regardless of how fast I listen to them, the duration of the words and the gaps between them stay the same relative to each other. You can experiment with this yourself with podcasts (but careful, lest you become a podfaster!), or by choosing a song or a piece of music and trying out a few different recordings on your favourite streaming service. The difference in speed can be huge, and have a real impact on how much you enjoy a particular song or piece of music.

And if there’s one thing to keep in mind when listening to music and thinking about quarter and half notes and all the rest of it, it’s that a song is always going to be a much bigger story than just its individual notes (and for more on music and stories, go to Tell me a story: music and storytelling).

It’s a living, breathing thing, a story that will never be told in the same way twice. It’s dynamic and fluid and compelling, and at the whim of the participants, just like every conversation you will ever have.