Picture this: you’re walking along the street and spy a small group of people staring up at the sky. What do you do? You’re searching for a restaurant and come across two next to each other, one almost empty and the other almost full. Which one will you choose?

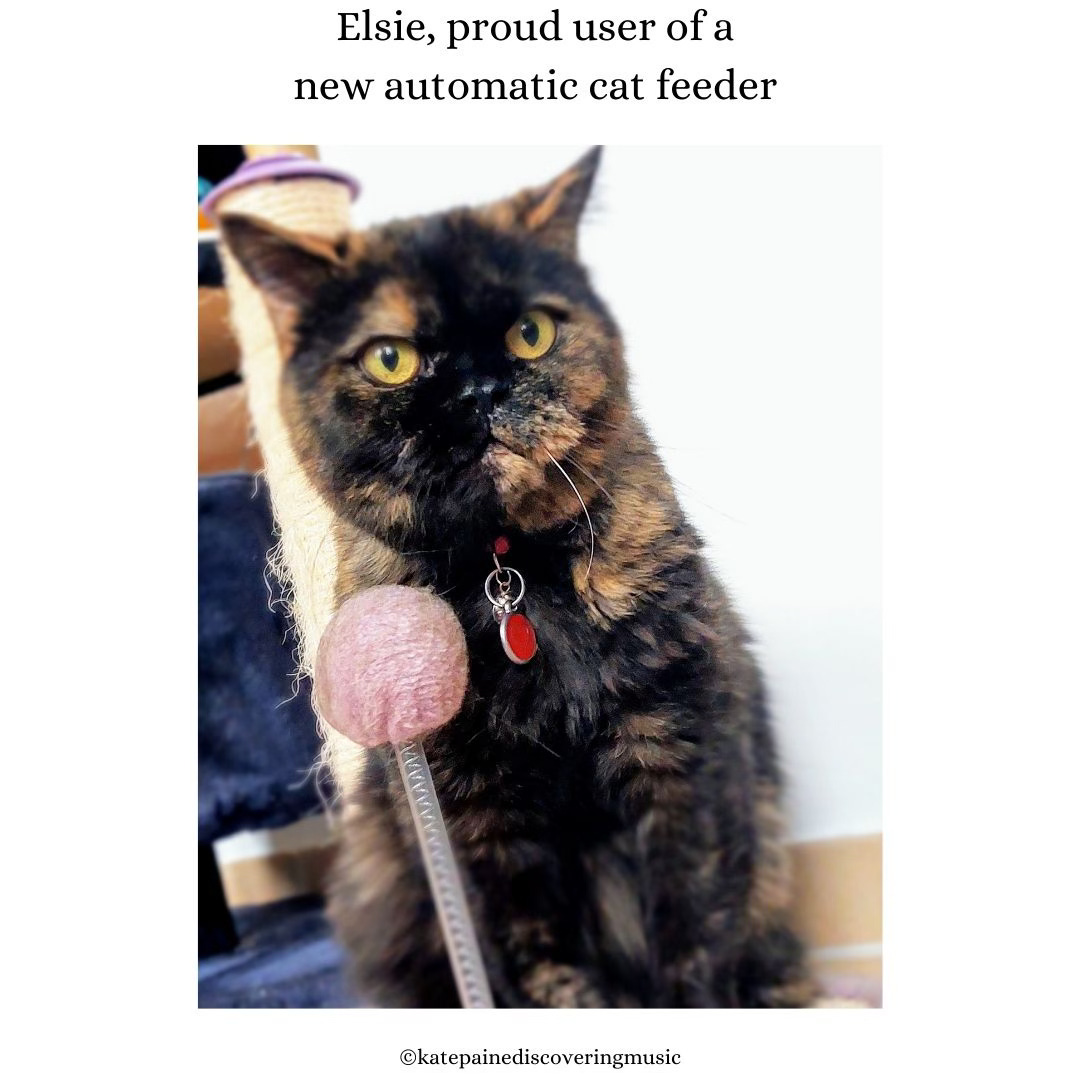

Or you’re thinking of buying a new automatic cat feeder to stop your cat waking you at five in the morning. Do you choose the one with no reviews or go with the one that has the most stars? (Shout out to Elsie, photo below, proud and hungry user of our new—and well-reviewed—automatic feeder!).

If you’ve ever found yourself following the crowd, being persuaded by an expert’s endorsement, or going along with a majority decision (even if you don’t quite agree with it), then you’re already in the grip of social proof.

Social proof is a phenomenon in which we find our actions influenced by the actions of those around us. It’s driven by our need for social validation and desire to conform to what we perceive to be the norms of a group or community. If we’re unsure what to do, we’ll follow the crowd, assuming that if everyone else is doing something a certain way then that’s how we should do it, too.

The Turkish-American social psychologist Muzafer Sherif was one of the first to really investigate social proof (you can read more about his research in his 1935 book The Psychology of Social Norms), although the actual name social proof came from the American psychologist Robert Cialdini in 1984.

But it’s been around for as long as we have, and for good reason; sticking together was obviously key to survival when survival was everything. Running in the same direction as everyone else in the face of potential danger (a charging mammoth, perhaps?) would have seemed like the smart thing to do.

No matter how much of a free thinker you know yourself to be, it’s almost impossible to avoid the social proof bias. Which means there’s a high chance you will be influenced by those you consider to have authority or credibility, and you will be susceptible to relying on the behaviour of others as a guide when you’re uncertain. You’re also likely to conform to the behaviour of the majority, even if it contradicts your own values and beliefs, and you’re probably going to be drawn to conform with those who you perceive to be like you.

Social proof taps into fundamental human psychological and social tendencies, so if you’re susceptible it’s because you’re human, and there’s no getting away from that, right?

How music works: social proof and how it can affect the way we participate in the world of music

Social proof can also play a powerful role in shaping how we approach and participate the world of music. Traditional music lessons usually involve following a pretty straight path consisting of lessons, practice, and regular external validation to ensure predetermined milestones are hit.

There’s a high value placed on note reading and technical work, and the music of choice is predominantly, if not exclusively, classical. This is how I started when I was five years old, and how I continued for all my years of lessons, including a music degree. There is absolutely nothing wrong with this style of learning if you enjoy it and if it aligns with your goals and interests, and if you’re prepared for the level of commitment required to keep up with it.

But I don’t believe it has to be for everyone. The trouble is social proof can nudge us to conform with what is perceived to be the ‘normal’ and ‘best’ way of doing things. When we see that the majority are travelling on this path, we tend to believe it must be the right way, or even the only way.

And this will be particularly so if we’re at all unsure, which is highly likely if you’ve had no prior experience or exposure and are therefore uncertain of what’s involved. And if we’re also uncertain of our own potential to learn and adapt, trying something new can seem like a scary prospect, so choosing a well-trodden path seems to make sense.

But it is not the only way to learn music, as I found out myself when I started playing in bands with friends. Suddenly I was being asked to sing and play with no music notes at all, to make up my own melodies and accompaniments, and to collaborate with other people doing the same. It was a whole new world, and one in which I felt very uncertain.

How could it be that I had been learning and playing music for so long and to such a high level but had never been encouraged to be creative? There were so many things I had no idea about. No one had ever suggested I experiment with notes and sounds and melodies or play without any notes in front of me; how would I know when I was making a mistake if I couldn’t see the actual notes I was supposed to be playing?

It was all a bit terrifying, but as I gained more confidence I became hooked; still terrified, but definitely hooked. Now music was as much about freedom and creativity as playing the right notes, and it was so satisfying.

Learning how to be creative and take risks and experiment are key elements of my lessons with my students, because music isn’t a narrow path, so why learn it as if it is? I value my own note reading and technical skills and theoretical knowledge, but I also value my ability to be creative and to approach and play music in many different ways.

So don’t let yourself be pressured or lead into thinking you have to do it one way or not at all. Instead, give yourself permission to prioritise satisfying your own curiosity. You might discover a great love classical music or you might not. You might find you thrive on exams and performances or you might not. You might find you love the intricacies of music theory and chord progressions or you might not. Or you might fall in love with playing only without notes, or not.

You won’t know until you get started. And once you do start learning, regularly evaluate what it is you’re getting out of your lessons, as well as what you would still like to experience.

And if you’re thinking of lessons for your kids, don’t be afraid to place just as high a value on creativity and fun as on practice and hitting milestones. Many of the adults I teach prefer a potent mix of learning, challenge, time (as in not rushing on to the next thing), forgiveness, reassurance, and familiarity, plus all the small joys that come along the way. So why not give your child the opportunity to experience these, too?

Or if you decide the traditional route is best for your child, then fully embrace it yourself as well instead of keeping it up on a pedestal. Show your child that you really value the process and the kind of music they’re playing; don’t keep it separate from your daily life.

There are so many pathways through the world of music. Make sure you don’t limit yourself to just one because it seems like the safe route or because everyone else is going that way, too.

Such a great way to explain herd mentality! It's often decried as bad, but it just is. It's just human. Knowing about it, seeing its edges, we can push back a little and experiment. (As long as there are no mammoths charging ;P ) I find it sooooo hard to improvise, this is a great reminder to try!